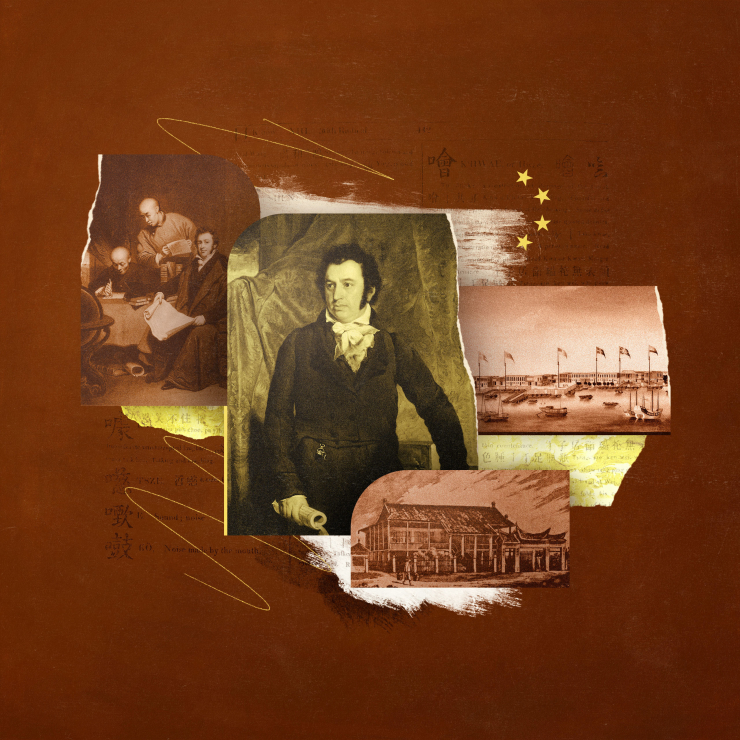

Who Was Robert Morrison?

On September 4, 1807, a ship called the Trident pulled into the port of Macao, a small Portuguese colony off the coast of China. Aboard the vessel was an Anglo-Scot Presbyterian minister named Robert Morrison. He intended to cross the border and go to the city of Canton, where he would begin missionary work among the Chinese people.

When others on the ship heard of Morrison’s plans, they were naturally skeptical. In those days, China was a mysterious and impenetrable world, sealed off from the West. Chinese law forbade westerners from residing in the country (except under very limited circumstances) and enforced strict laws on its citizens to prevent them from embracing Western ideas. Practicing foreign religions or teaching a westerner the Chinese language were crimes punishable by death.

From a human perspective, Morrison’s mission seemed impossible. Someone asked him cynically, “And so, Mr. Morrison, do you really expect that you will make any spiritual impact on the idolatry of the great Chinese Empire?” “No sir,” Morrison replied, “but I expect God will.”1 Indeed, God made an impact through the faithful labors of Morrison, who became the first Protestant missionary to China.

Early Life and Formation

Born on January 5, 1782, in the small town of Morpeth, England, Morrison was the youngest of eight children. His father, who was Scottish, and his mother, who was English, were active members of the Church of Scotland and raised their children to know the Bible and the Westminster Shorter Catechism. It is said that at the age of twelve, Morrison could recite from memory all of Psalm 119. By age fourteen, he left school for an apprenticeship in his father’s business. About two years later, he was converted. “I was much awakened to a sense of sin,” writes Morrison:

I was brought to a serious concern about my soul. I felt the dread of eternal condemnation. The fear of death compassed me about and I was led nightly to cry to God that he would pardon my sin, that he would grant me an interest in the Savior, and that he would renew me in the spirit of my mind . . . It was then that I experienced a change of life, and, I trust, a change of heart, too.2

After making a profession of faith, Morrison soon felt called to the mission field. In 1801, he began studying Greek, Hebrew, and Latin. In 1803, he entered the Hoxton Academy in London to be trained as a minister. Shortly thereafter, he was recruited by the London Missionary Society to go to China and lay the foundations for missionary work. Elated, Morrison wrote to a colleague: “I wish I could persuade you to accompany me. Take into account the 350 million souls in China who have not the means of knowing Jesus Christ as Savior.”3 After several more years of preparation and studying the Chinese language, he was ordained in the Scots Church in London in 1807 and sent to China as a missionary.

Missionary to China

From day one, Morrison’s ministry was beset with discouraging obstacles. Jesuit missionaries based in Macao opposed him immediately. He set out for the city of Canton but was prohibited from entering. Foreign merchants were restricted to a narrow strip of land outside the city walls where they traded with the Chinese in factories. Morrison lived in the basement of one of these factories while he studied Mandarin and Cantonese in secret from tutors willing to risk their lives. He was often cheated, frequently ill, and had to live in almost complete seclusion to avoid detection. His loneliness was overbearing and affected his health. Nevertheless, he pressed on. He began compiling a Chinese dictionary and translating the Bible. In his prayers, he often pled with God in his broken Chinese, asking for help to master the language and be more effective.

God answered Morrison’s prayers. He quickly became so proficient in Chinese that in 1809, the East India Company, which controlled all trade between the British Empire and the Orient, offered him the post of Chinese Secretary and Translator with a salary of £500 a year. This provided Morrison with legal grounds for remaining on Chinese soil. That same year, God also gave Morrison a wife. He married Mary Morton, the daughter of a surgeon in Macao. Together they had three children.

Spiritual Impact

After seven years of missionary work, Morrison baptized his first convert. Over his twenty-seven-year ministry in China, he would only baptize ten. Yet, Morrison’s labors were not in vain. He published a three-volume Chinese dictionary, a Chinese grammar, a translation of the Bible, and many articles in missionary journals throughout the world to promote the cause of the gospel in China. He also founded the Anglo-Chinese College at Malacca. The Lord used Morrison as a pioneer, paving a way that would bring many missionaries to the people of China.

Morrison’s wife, Mary, died in 1821. In 1824, he married Eliza Armstrong, with whom he had five more children. Morrison died on August 1, 1834, at the age of fifty-two, from a fever and exhaustion. He was buried next to his first wife, Mary, and infant son, James, at the Protestant cemetery in Macao. His grave can still be visited today.

This article is part of the Missionary Biographies collection.

- R. Li-Hua, Competitiveness of Chinese Firms: West Meets East (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 40.↩

- Wikipedia. 2023. Wikimedia Foundation. Last modified April 7, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Morrison_(missionary)#cite_note-babelstone.co.uk-7.↩

- Hallihan, C.P., “Robert Morrison Bible Translator of China, 1782–1834,” Trinitarian Bible Society Quarterly Record, Oct. to Dec, 2008, Issue 585, 17; www.trinitarianbiblesociety.org/site/articles/morrison.pdf.↩