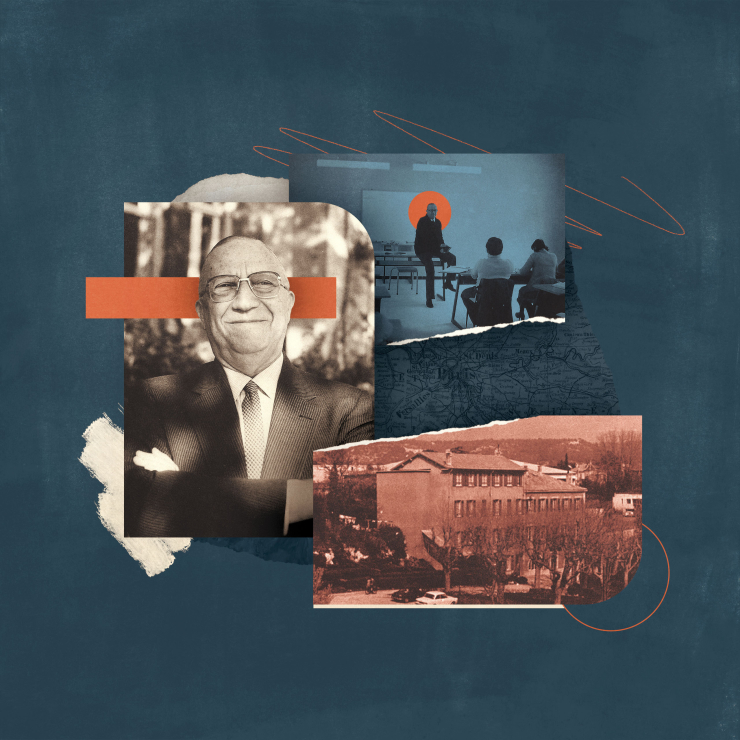

Who Was Pierre Courthial?

Pierre Courthial1 (pronounced CORE-tee-all) was a stalwart Reformed theologian and pastor in France in the twentieth century. He was born in 1914 in Saint Cyr-au-Mont-d’Or, on the north side of Lyon, to a religiously mixed household—his father was French Reformed and his mother Roman Catholic. He was raised in the French Reformed church and at the age of sixteen, he encountered the writings of John Calvin and Pierre Viret. Their combined theological vision would exercise a dominating influence on his own vision.

Service as a Churchman

As a student at the Protestant Faculty of Theology in Paris, Courthial came under the influence of the great French Reformed theologian Auguste Lecerf and developed a lifelong friendship with fellow student and future Reformed theologian Pierre Charles Marcel.2 Courthial graduated with a scholarship in hand to pursue his PhD at the Free University in Amsterdam. However, doctoral studies in Amsterdam were not to be. Courthial heeded an unexpected call to serve as an interim pastor in Lyon, which inaugurated a lifetime of service as a churchman—interrupted only by his service in the French Army during the Second World War, during which he took part in the famous Dunkirk Evacuation.

In 1941, he became the pastor of a Reformed parish in La-Voulte-sur-Rhône, a city in the region of France then under Nazi occupation. Amidst his pastoral duties and the unusual strains of that time, Courthial nonetheless devoted two hours every morning to personal study, a practice he would maintain throughout his entire ministry. He read widely in theology, philosophy, and literature, availing himself to works in French, Dutch, German, and English.

In 1951, Courthial joined the pastoral staff of the eminent Reformed Church of the Annunciation in Paris in the upscale sixteenth district of the city not far from the Arc de Triomphe. In 1956, he would become the senior minister of that congregation, serving until 1973. During those years of ministry, Courthial was a significant leader promoting cross-denominational engagements of a biblically serious kind through his writings and organized ministry efforts,. He declared, “[W]e reject the fashionable ecumenism of the day, seeing as how it is unfaithful, insipid, soft and spineless. Instead we press forward in the faithful, vigorous and confessing ecumenism to which Christ Jesus and the Sacred Text call us.”3

Writings

A man of courage drawn to men of courage, Courthial was often disappointed when those who confessed the authority of Scripture shied away from exploring its specific application in their own areas of work and life. But he also maintained a characteristic warmth and good humor that accompanied his buoyant hope in God’s promise that, despite all else, the “earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of God as the waters cover the sea” (Hab. 2:14). His writings in this period, gathered and published as Fondements pour l’avenir (“Foundations for the Future”), reflect his wide range of interests in theology, biblical studies, and ethics, including his forceful refutation of the neoorthodox theology of Karl Barth.

After a quarter-century of distinguished ministry in and beyond Paris, Courthial was asked to lend his formidable name to the founding of a small conservative faculty of Protestant theology in Aix-en-Provence (now called la Faculté Jean Calvin). “Its declared purpose at the beginning,” says William Edgar, “was to renew the Reformed churches of France by graduating convinced gospel-driven men who would occupy key pulpits.” Courthial put his hand to the effort, moving to Aix and serving as professor and dean. In 1979, he traveled to the United States to receive an honorary doctorate from Westminster Theological Seminary as part of the seminary’s fiftieth-anniversary celebration. After a decade of service in Aix, Courthial retired to Paris in 1983.

Retired from active ministry, Courthial wrote his two major works from Paris, A New Day of Small Beginnings and The Bible: The Sacred Text of the Covenant. The first of these was written to encourage Western Christians living in an era of all-pervasive but increasingly exhausted secularism to hold fast to their confidence and serve the Lord obediently in every area of life. G.I. Williamson deemed it “one of the greatest books I have ever read” and Douglas F. Kelly predicted “would be a highly significant book in the Church for the next fifty years,” Surrounded as he was by an atmosphere of total secularism in Paris, Courthial presses for a kind of total Christianity that finds its basis not only in sola Scriptura (Scripture alone) but tota Scriptura (all of Scripture, the Old Testament as well as the New) and builds upon the traditio e Scriptura fluens (the church’s dogmatic tradition flowing from Scripture).4 Tracing out the history of God’s covenantal ways from creation to Christ and through the upheavals of the twentieth century, Courthial summons the church at the beginning of the twenty-first century to respond to humanism, with its ideological commitment to autonomy in law and ethics, with a comprehensive and doxological articulation of the law of God applied to every area of life.

Impact

Courthial expected that this effort will, like the development of the grand dogmas of the Trinity and of Christ in the early church, and the grand dogmas of Scripture and of salvation in the Reformation period, take time. But he also expects that the Lord will bless those who humbly submit the whole of their lives—beginning with their hearts, homes, and churches, and extending out into their spheres of influence—to the whole of His Word.

On the basis of God’s abiding covenant of grace, Courthial expected that such humble, faithful obedience in the present—an obedience of “small beginnings”—will be seen in hindsight as the planting of “the seeds of the next Reformation.”5 He wrote, “As Humanism approaches, and perhaps fast approaches, the end of its road strewn with ruin and death, it is this next Reformation that will replace it. On this renewal depends the future of the life of the world.”6 In his second book, The Bible: The Sacred Text of the Covenant, Courthial more fully articulated the grand “theocosmonomic vision” that he believed will undergird this coming renewal.7

Courthial died on April 23, 2009. At his memorial service, theologian Paul Wells delivered these words:

In a France so rapidly and thoroughly secularized after 1968, it was impossible that the gifts and capacities of a man with Pierre Courthial’s convictions would be appreciated and utilized. If he had lived in the nineteenth century, we’d be talking about Courthial alongside Spurgeon; if he’d lived in the eighteenth century, alongside Whitefield; if in the sixteenth century, alongside Calvin, Luther, and Bucer; and if in the fourth century, we’d speak of Courthial alongside Athanasius.

But in the twentieth century, Christianity in Europe experienced no revival, but only continual decline. Who wanted to take seriously a pastor-theologian who longed for the Church “to be reformed according to the Word of God”?

Indeed, Courthial longed with undiminished hope for the church “to be reformed according to the Word of God.” If his preaching and writing was not taken seriously by his countrymen in his own generation, it may be that our sovereign Lord purposed instead, as he did with another Frenchman by the name of Calvin, to establish the work of his servant’s hands in lands beyond his own.

This article is part of the Historical Figures collection.

- Image Credits: Pierre Courthial, Classroom/Pierre Courthial, Aix-en-Provence Seminary↩

- Four of Marcel’s works have been translated into English: Baptism: Sacrament of the Covenant of Grace, trans. Philip Edgcumbe Hughes (Mack, 1951); The Relevance of Preaching, trans. Rob Roy McGregor (Baker, 1963); In God’s School: Foundations for a Christian Life, trans. Howard Griffith (Wipf & Stock, 2009); and Marcel’s monumental study of Herman Dooyeweerd, The Christian Philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd, 2 vols., trans. Colin Wright (Wordbridge, 2013).↩

- Pierre Courthial, De bible en bible (Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme, 2002), 153. Forthcoming as The Bible: The Sacred Text of the Covenant (Tallahassee: Zurich Publishing, 2023).↩

- Pierre Courthial, A New Day of Small Beginnings (Tallahassee: Zurich Publishing, 2018), 162-165. “When we say ‘according to Holy Scripture,’ we must mean according to the whole of Scripture—nothing more (sola), nothing less (tota)” (164).↩

- Ibid., 305.↩

- Ibid.↩

- Courthial coins the term “theocosmonomic” by adding “theos” (God) to “cosmonomic” (cosmos, world + nomos, law), which was a central concept in the work of the Dutch Reformational philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd (1894-1977).↩