Saved by Grace Alone

3 Min Read

In this brief clip from his teaching series A Survey of Church History, W. Robert Godfrey examines the difference between a theology that believes salvation is by grace alone and a theology that believes salvation is mostly by grace. You can watch this entire message for free.

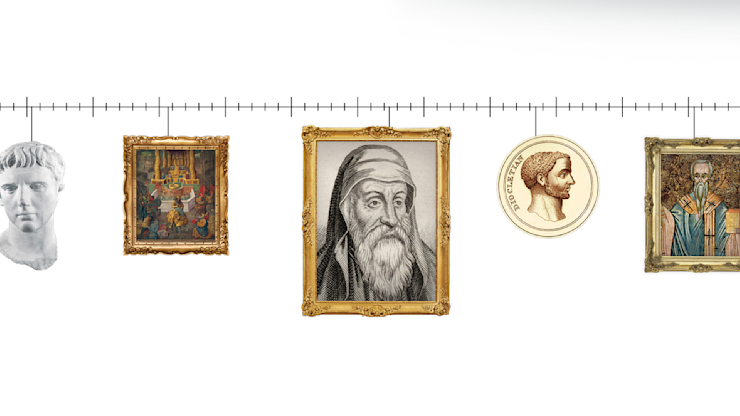

Augustine taught that we are saved by grace alone. He was absolutely unambiguous and clear about that. And the later medieval Augustinians, many of them taught we are saved by grace alone mostly. Now you can see, if you like yourself and think your theology is pretty good, that you would think the difference between saved by grace alone and saved by grace alone mostly is not much of a change, right? That’s what these Medievals, many of them -- there were people who did follow Augustine in the Middle Ages (we’ll come back to that as well) who did say in the Middle Ages absolutely we’re saved by grace alone. But many said we’re saved by grace alone mostly and really thought that they were Augustinian, that they weren’t betraying anything essential. What they meant, and what people like Gregory meant by that is, we cannot be saved except by grace. And you see that is Augustinian to a point. Pelagius had said we can be saved without grace, they don't happen very often but it's theoretically possible we can be saved without grace. After the debate between Augustine and Pelagius, nobody in the West argued you could be saved without grace. In that sense, Augustine had won the absolute victory. You have to have grace to be saved. But the question is, if you have to have grace to be saved, where does it come from? How do you get it? How do you keep it? That's where there was a movement away from the fullness and clarity for what Augustine had said.

For Gregory representing the kind of theology that would be frequently promoted in the life of the Church, Gregory said “Well, you see, grace is received in baptism.” So, of course, you have to have grace to be saved and you get grace in baptism. So you have to be baptized to be saved and everybody gets grace in baptism and then what are you going to do with that grace? You have to make appropriate use of that grace and the appropriate use of that grace is in constantly confessing your sin, constantly hoping by grace to lead a better life, constantly making use of confession and the sacraments of the church to be progressing in the Christian life. And what you had then in the theology of Gregory is a theology in which the whole of life is a struggle, is a repentance to hold on to the grace one has, to seek forgiveness for the sins one continues to commit. A noble lady wrote to Gregory and asks him to pray for a revelation to him from God that she was saved. It’s a very interesting letter where he writes back to her and says “It would not be good for you to know that you are saved. It is good that you live in doubt about your salvation so that it's a motivation for you to keep working, keep struggling, to keep laboring so that you will never be presumptuous in your relationship with God but that you’ll always be seeking more grace. But you see its grace that’s achieved through a measure of cooperation. It’s a grace that’s never stable or secure.”

This is the foundation that Gregory began to lay for the church. A foundation of a stress-on-grace but of a kind of Christianity that is a constant struggle, a constant worry, a constant effort in hopes that you would die in grace and be saved but never with an assurance in this life that that's true.